I never set out to paint Zambia in a light of beauty. Beauty is subjective and finds a way to show itself without effort. There are many photos of Africa that have circulated throughout time, capturing a single narrative of poverty, starvation, and disease… pinning that as the way of life on the continent. The photos displayed in this post are not with the intent of perpetuating the stereotypes of those images, but the intent is to share my reality. -KENYA

In continuation of the post entitled “Living with Load Shedding – Part 1”

Click Here to read Part 1.

Economic Effects

While load shedding gravely impacts personal lives, the socioeconomic losses that Zambia is experiencing are astronomical. Businesses have closed, workers have been laid off, and prices of essential commodities have doubled. When I arrived in July, the price of a box of juice was 14 kwacha (the equivalent of $1.40 USD depending on the economy). That same box of juice recently rose to 27 kwacha (the equivalent of $2.70 USD). This may not seem like a lot, but consider the fact that Zambia is a lower-middle income country where residents lives off less than $2 per day. Strong emphasis should be placed on ‘depending on the economy’ as the kwacha has been depreciating daily, sometimes hourly, in value against the US dollar. The majority of items sold in Zambia are imported from other countries. Some would even debate that our import of goods are in excess and nearly everything we use/consume is likely made in another country. Thus when the kwacha loses its value, businesses increase the prices of those imported goods to maintain a profit.

Here’s another comparison to put things into perspective. When I arrived in July, the exchange rate between the local currency and the US dollar was 7.5 kwacha, meaning 1 USD would trade for 7.5 kwacha. The current exchange rate as of January fluctuates between 11 or 12 kwacha with the highest recorded being 14 kwacha.

Personally, I’ve had to shift a bit in spending in that when I was in the US the value of my dollar never changed. I knew that as a patron at the local grocery store, my $1 would always be $1. I could plan monthly the amount to allocate towards food, household goods, etc. Now, I’m like a gambler without a strategy, always checking ‘the numbers’ to see how much my 1 kwacha be worth for the day, or trying decide if I should purchase those cashew nuts today or wait to see if the rate will work in my favor.

The largest economic hit has been experienced by the mining industry. Zambia is the leading producer of copper on the continent with 80% of export earnings generated from the metal. Many of its residents are dependent on the mines for job security. Due to the power crisis, mines are not able to operate in full production and have been forced to lay off thousands of workers. The ripple effect of unemployment as a result of load shedding is not isolated within the mining industry but other areas such as education and health feel the weight as well. Children are dependent on the financial earnings of their parents/guardians to pay mandatory fees to attend school. When parents can’t afford to pay required school fees, children are forced to drop out of school. This in turn increases the chances of low literacy rates and the chances that a child will not be able to reach its full potential in society through access to education.

I recall reading a story in the local paper about one of the most intense experiences of students and teachers during load shedding. It was noted that over 400 grade 9 students arrived one morning to take their computer-based final exams. Power was unexpectedly cut and load shedding was in full effect. The school had one generator with the capacity to power only 8 computers in the absence of electricity. To ensure that every student completed their test, final exams lasted until 4am the following day.

The cumulative effect of the depreciating value of the kwacha currency, load shedding, and plummeting prices of copper, Zambia’s economy is at a desperate state.

Work Life Effects

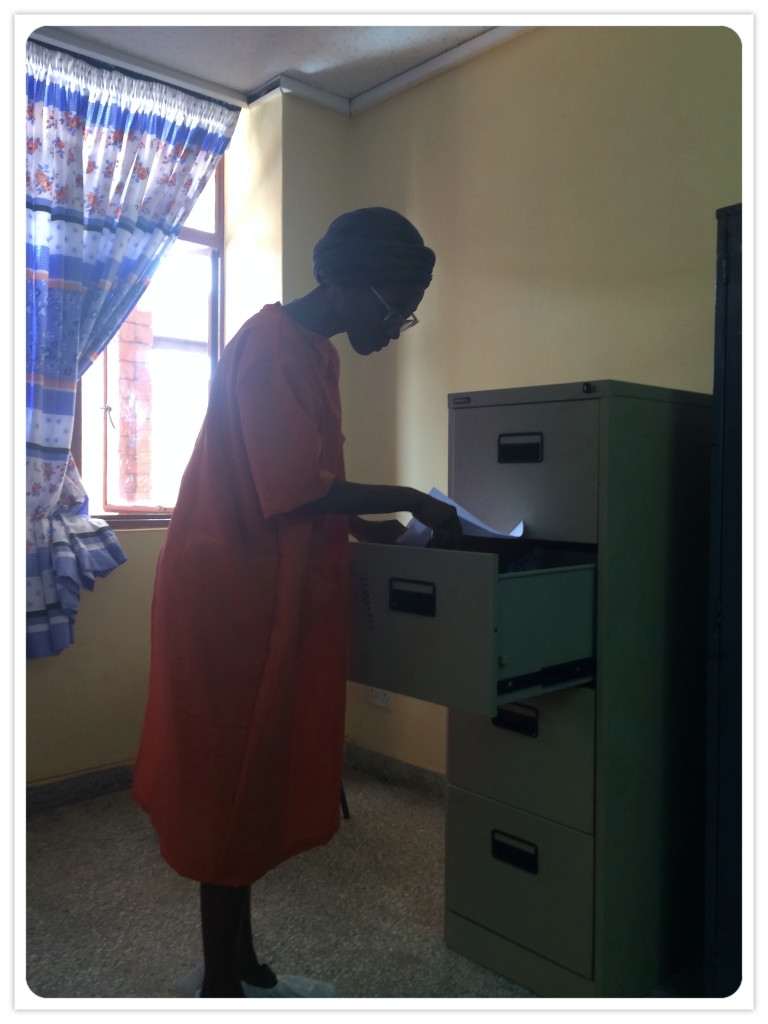

As an Epidemiologist, I spend many of my working days at the local hospital and at a clinic in the Chawama Compound. These two areas are juxtaposed in that the hospital is located in an urban more developed setting and the clinic is in a peri-urban less developed setting.

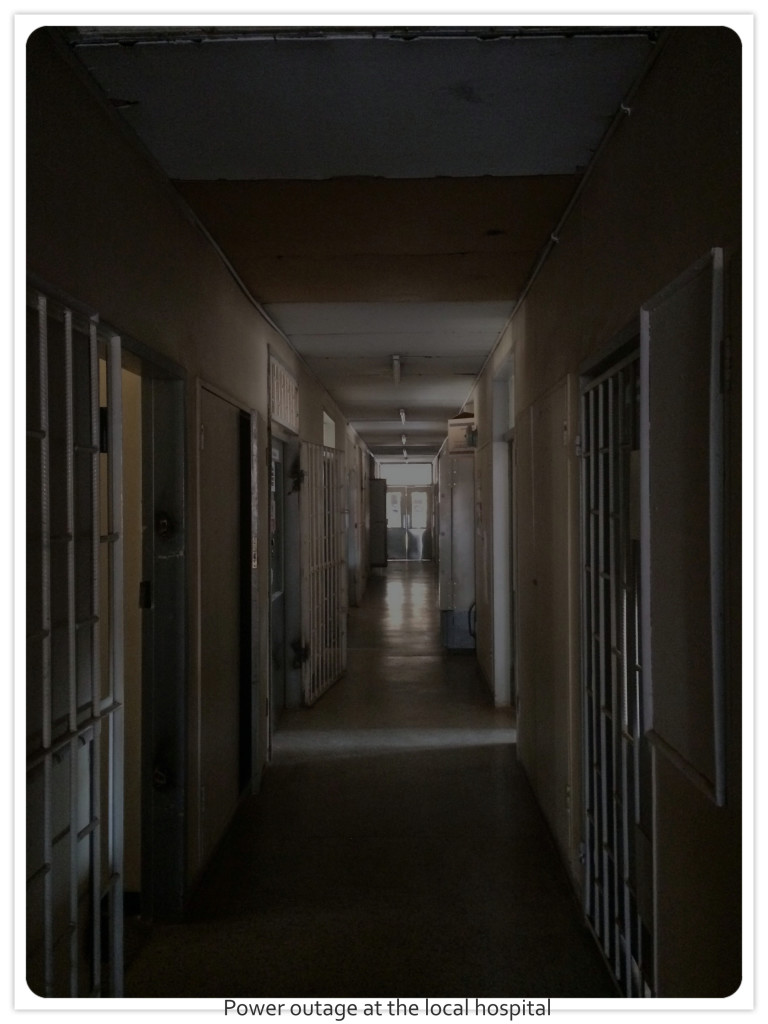

Facilities such as hospitals are protected from load shedding and are supplied with a generator to combat the effects. However, there are instances when mishaps happen with the power company and the back up generator for the hospital shuts off. On days as such, we are forced to work by the light of day which unfortunately means that the there is a strong chance that there is a patient somewhere in the ward who will not make it to see the light of the next day.

I strongly empathize with the students and the educators who labor in finding workarounds during load shedding.

Vulnerable units such as the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) where sick babies are kept in incubators and the operating theaters where patients are undergoing surgery are at greatest risk of ill-fated outcomes when electricity goes off.

I was recently asked “How do you cope emotionally working in such environment where your efforts are beyond your control?” I pray. When the lights flick and the corridors of the hospital become dark due to no power, and the scurrying of the feet of nurses who are trying their hardest to keep a patient afloat until electricity is returned can be heard all throughout the ward, I’m praying. It helps that my prayers are not in secret or in self-contained whispers, as Zambia is a Christian nation and we openly pray in all spaces.

Often I feel as if I’m in the midst of catastrophic failure. I’m trained to provide answers and to figure out ‘the why’ of events. When I hear of a patient on the ward who has passed away or when the numbers roll in on a study in which I’m involved and I see the count of deaths, my immediate thought is always “Was the power cut when this person expired?” In many of these cases, I leave without an answer.

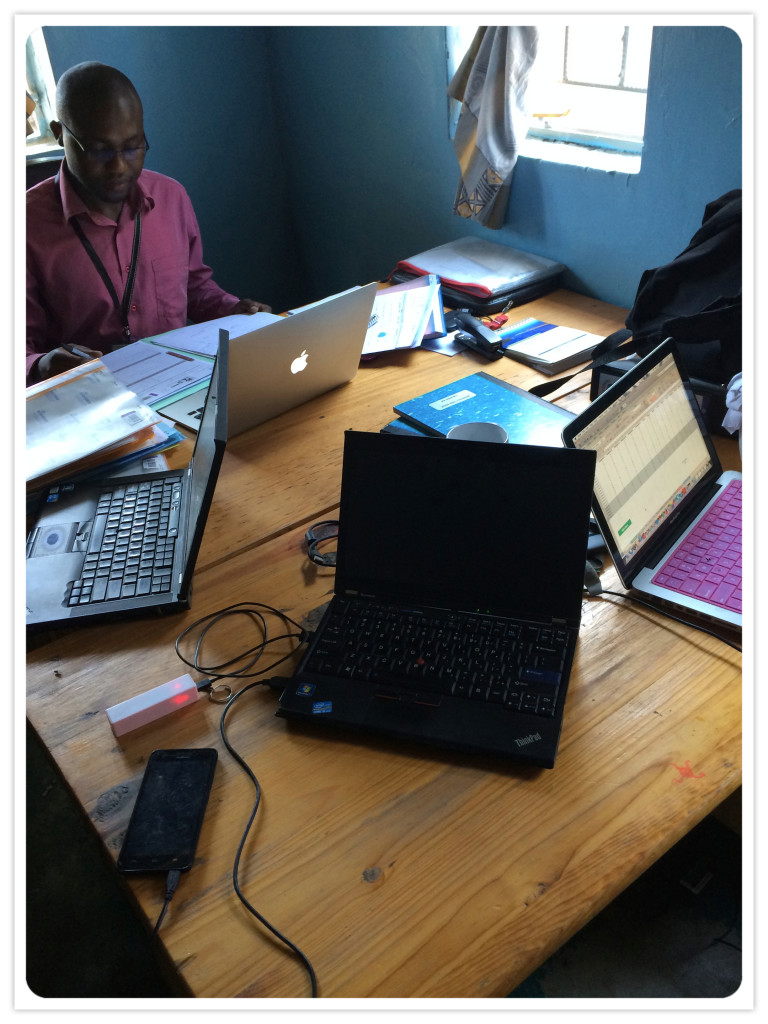

Productivity. (Millennial example) Imagine needed to send an urgent email or having a deadline to meet with international partners, yet electricity is not available. In a sense I think load shedding has brought many unrelated organizations together. In NYC we would call this behavior ‘Co-working’, in which professionals of different organizations share one office space. In Zambia, out of sheer generosity we find ourselves inviting neighboring organizations over who are not able to access electricity to use our source of power just to be able to maintain operations. Such an act of kindness has given me the opportunity to cross paths with professionals in sectors I would have never imagined.

Not much has changed since I initially wrote this post.. other than our spirits are more optimistic and we’ve found craftier ways of getting around using electricity. Innovative sounds like a more appropriate word. Other countries in Africa deal with load shedding but on a different scale. In Ghana, load shedding is called ‘dumsor’. It’s unscheduled and generally lasts about 3 hours per day; whereas we are up to 10 hours in Zambia. However, they’ve been battling ‘dumsor’ for years in Ghana whereas this is a new phenomena that began in 2015 for Zambia.

I will keep you updated on load shedding as changes occur.

Rachel

June 12, 2016 at 3:19 pm (9 years ago)I can only imagine what it’s like for something like this to be my reality. Living with load shedding on a personal level is one thing but having to deal with it at work it’s another. Here in America that would automatically register as a day off WITH pay. To hear how in Zambia this reality creates an opportunity to be innovative, work harder and increase community through “work sharing” or just engaging in more direct contact puts a different spin on gratefulness . This was such an eloquent yet informative article. I can appreciate your honest perspective of your journey in claiming your new normal. Love you sis.